The George Inn, a Public House, Portsmouth, Hampshire • April 15th, 1797, Easter Saturday

My Client and I arrived in Portsmouth at ½-past 5 o’clock yesterday Evening after a Journey of more than 70-miles along the Portsmouth-Rd. from London. I had advised we travel on Horseback, but my Companion was most eager to take the “Stage-Coach”, this being a novel Mode of Transportation in that Person’s experience. All my Arguments fell on deaf ears and I had no Choice but to secure Seats on the Coach.

Our Trip was a far greater Ordeal than even I expected. What was to be a 9-hour Journey—we were due to arrive at The Fountain in time for Tea on Wednesday—ended up taking 3-days.[1] We are now staying at The George on the Portsmouth high Street, not far from the Church of St. Thomas à Becket. Since my Patron is yet to join me this Morning, I will describe our Journey.

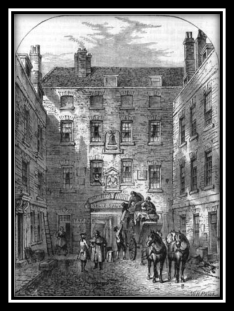

We set out on the Rocket from London at ½ -past 8 o’clock in the morning from La Belle Sauvage; she is an Inn on Ludgate-Hill, not far from St. Paul’s.[2]

Figure 19. Outer Court of La Belle Sauvage Inn in 1828, by Mr. W. H. Prior, from an Original Drawing in Mr. Gardner’s Collection, in Mr. Walter Thornbury, Old and New London: A Narrative of its History, Its People, and Its Places, &c., Volume I, 1868, p. 217

Passing through Wandsworth and Stone’s End, we crossed the Thames by the wooden Bridge at Putney where our first Toll was paid. Our Diligence next traversed Putney Heath and Wimbledon Common, fortunately without Event, the latter being notorious for Footpads and Highway-Men.[3]

We passed through 6-Turnpikes in total, with further Stops every 10- to 12-miles at Coaching-Inns for the change of Horses, the first being the Robin Hood in Kingston-Vale. Our Route took us through Esher, Ripley, Guildford, Godalming & Petersfield, among other Towns, Villages and Hamlets.

I had my Copy of the most recent Edition of Mr. Paterson’s A New and Accurate Description of all the Direct and Principal Cross Roads at the ready.[4] It includes Points of Interest along our Way, such as the Obelisk of Wimbledon, and the Country-Seats of various Nobility and Gentlemen. However, ours was not a Journey amenable to Sight-Seeing.

Our Coach was drawn by 4-horses. Its human Freight consisted of 6 human Passengers and one child within, 4 without—3 very rowdy young Midshipmen, one of which was severely inebriated, and a Gentleman’s Valet—as well as the Coachman and Guard, who doubled as Postilion. The nameless Persons with whom we were jarred and rattled within the cramped, stuffy Quarters of the Rocket consisted of—:

An elderly Woman travelling with a malodorous Lap-Dog. A Woman of middle-age, presumably a Nurse, accompanying a grizzling Infant with a dreadful chesty Cough, also travelling on a Lap. A Gentleman of dubious Hygiene who slept, snoring loudly all the while. A second Gentleman of impressive girth with a Hamper of Fish.

Needless to say, we were assailed on all sides by unpleasant Sounds and Smells. The old Woman and my Client were both compelled to cover their nose with their Handkerchief, but this was the least of our Woes.

Our Progress was slowed by the effects of recent heavy Showers. As a consequence of the muddy Roads, we were obliged at various times to “ease the horses”, viz. to get out of the Carriage while the Horses negotiated rutted Inclines and Declines, and pools of liquid Dirt.[5] The floor of the Coach was a Sea of Mud in no time, but although unwelcome, these Punctuations in our Journey had the effect of airing the Carriage of its human and animal Aromas, although not of the Fish, the Hamper remaining within at all times.

To add insult to injury, the Axle broke almost a mile out of Liphook. My Client and I chose to tramp into that Village and took a Brandy at the Royal Anchor. The Midshipmen soon followed. When my Companion saw their youthful Spirits fortified by more Liquor, it was decided we stay the Night at the Inn. Fortunately, our Host was affable and our Rooms comfortable enough. Unfortunately, we were compelled to stay a second Night, being unable to secure seats on the Coach until yesterday Afternoon, when 3-passengers terminated their Journey here. The Remainder of our Journey to Portsmouth was without Event.

This Morning we shall view Mr. E. N. Greensword’s Ship. She is H.M.S. Royal George, Flagship of the Reserve Channel Fleet, under the Charge of Admiral Alexander Hood, the Viscount Bridport, the most senior Commander under which your Forebear has served as yet.

According to last Saturday’s Edition of The Hampshire Chronicle, “the greatest Despatch has been used in victualling &c. [Bridport’s] Squadron for Sea. In addition to the Force with which he returned to Portsmouth, he is to have 9 fresh Ships for his ensuing Cruize; making, in the whole, 23 Sail of the Line”.[6] The Fleet will sail via the Spithead “sea-road” for St. Helen’s, Isle of Wight, and from thence into open Sea.[7]

Reader, I have it on good Authority the Squadron will sail this very day! I am much relieved our arrival in Town was not delayed any more than it was, or we would have missed the Boats!

§

You are chilly? I am not surprised, for the Sun is Weak and the Breeze is High. It is Spring in Hampshire and we are on the Coast of England, after all! I do not go so far as to say April is the cruellest Month, but she lacks the relative Constancy of Winter and Summer, not to mention the mellow fruitfulness of Autumn. We must be grateful the Weather falls short of Inclement, for today you will witness the Departure of the Reserve Channel Fleet from Portsmouth. It will be a remarkable Sight! I say, where is your Cloak?

Then we shall seek out a more sheltered Vantage-Point from which to view the aforementioned Spectacle; I must insist, however, we keep H.M.S. Royal George within eye-shot. What do you mean, you do not much care? Ah, but you must! Unless he be in his Sick-Bed, which History does not indicate, your Relative is already on-board this Ship! There may be Opportunities to catch a Glimpse of Mr. Greensword, whom we were unfortunately unable to see properly at his Wedding. There are just three Masters’-Mates on-board the Flagship, identifiable by the white Trim on their navy-blue Frockcoats. This suggests to me that the odds of glimpsing our Protagonist on the Quarterdeck are quite good. You did bring your Spy-Glass?

As you can see for yourself, H.M.S. Royal George is a very, very, fine Vessel, indeed. She is a First-Rate Ship of the Line with 100-guns, built at the cost of £51,799.5s.7d. At the time of her completion 9-years-ago, viz. 1788, she was the largest Ship ever-built for the Royal Navy. Your Forefather, the Masters’-Mate, must have felt immense Pride the Day he first boarded H.M.S. Royal George. It was the 19th of November 1796;—at least according to the Archives of the Royal Navy.

Mr. Edward Greensword was sent there from H.M.S. Moselle, a 24-Gun French Sloop captured 1794, upon which Vessel he served for an Interval of just three Months. He had come from H.M.S Sceptre, a 64-gun Third-Rate Ship of the Line, where he served under Captain William Essington for a Period of 2-years—from the 18th of July 1794 to the 19th of August 1796—and was promoted from Midshipman to Masters’-Mate.

Thanks to Mr. Wm. James, who is compiling a History of the Royal Navy, it has come to my Attention that both H.M.S Sceptre and H.M.S. Moselle were in the East Indies in August 1796. It therefore seems plausible to me that Mr. Greensword was sent to the Moselle for the purposes of his return Journey to England. What were they doing in the East Indies?

They were among a large Convoy under the Command of Vice-Admiral Sir George Keith Elphinstone, lying in Simon’s Bay, off the Cape of Africa. Upon learning a small Squadron of Dutch Men-of-War were anchored in Saldanha Bay, the British put to Sea. They arrived off Saldanha Bay on the evening of the 16th of August, and forming a Line, “anchored within Gun-Shot of the Dutch”. On account of “the great disparity between the two Forces”, the Dutch Rear-Admiral agreed to a Surrender on the 17th of August,[8] just two days before Mr. Greensword went to the Moselle.

This was not the first time your Ancestor encountered the Dutch. Let me tell you of another.

On the 12th of March 1795, Sceptre sailed for the Cape of Good Hope as an Escort for a fleet of East-Indiamen bound for India and China. Three-months later shewas part of a Convoy including East-Indiamen, General Goddard and Burbridge, and the Packet, Swallow, sitting off St. Helena. On the 15th of June, the English Shipsengaged & captured 7-Dutch East-Indiamen. According to one of my naval Consultants, Mr. Luddock, “the prize money, two-thirds of the value of the Dutch ships and their cargoes, came to £76,664.14s., of which £61,331.5s.2d.” was awarded to the aforementioned British ships and the Asia.[9]

Lieutenants, Warrant Offices & Masters’‑Mates shared in the one-eighth of the Prize Money allocated to them, which no doubt reduced to a modest amount given the five Ships. Young Mr. Greensword might nevertheless have received a Sum not far off his annual Income![10]

Figure 20. Mr. Thomas Luny, H.M.S. Sceptre, and Swallow capturing Dutch East Indiamen. Oil on canvas, 45” x 72”, circa 1796, National Maritime Museum

In truth, it is not uncommon for the Distribution of Prize-Money to take an inordinately long time. Perhaps it was only upon Receipt of his monies and his Appointment to his new Station that Edward felt able to marry. As the Case may be, Mr. Greensword was sent to the Royal George scarcely a Fortnight before his Marriage. I trust his heart was filled with much Optimism for the Future. As for Miss Hopkins—; What was that?

Yes, quite so. I did not anticipate this Delay. Perhaps my Intelligence was faulty, but I must say the Officer I spoke to late last night seemed a most reliable and sober Source as to the Squadron’s intended Departure time today. I went downstairs at ½ past 11 o’clock for the express purpose of ensuring there were no Impediment to the timely Exodus of Bridport’s Fleet. No, not at all. It was absolutely no trouble whatsoever. May I resume my Narrative? Very well.

The Newly-Weds, you will recall, left Town soon after their Wedding. It is likely they arrived in Portsmouth in the early hours of the 1st day of December 1796. However, I must allow that Mr. & Mrs. Greensword may have dawdled in order to take in Sites along the Portsmouth-Rd. such as the Wimbledon Obelisk.

By now, Mrs. Greensword is safely installed in their Accommodations. I cannot say exactly where, though Gosport seems to be fashionable at present. She may, however, spend the Duration of her Husband’s Cruize in Portsea. One may safely assume the Newlyweds arrived in Portsmouth with a Letter of Introduction from Mr. Joseph Greensword commending them to his old Friend, M. Charrier, the French-Master at the Royal Naval Academy in Portsea. What a boon is would be were Sarah Ann to have come under the Wing of Mme. Elizabeth Charrier and her learned and pious Husband? [11]

I hope, too, that Mrs. Greensword has come to the Notice of a kindly and respectable Society Matron able to see to her inclusion in polite Society, not to mention a mature and experienced Naval Wife able to instruct her in such Niceties as the provision of a Hamper of durable Comestibles for her Husband upon his Departure on a Cruize.

Today our young Masters’-Mate goes to Sea, having no doubt farewelled his young Wife with regret, but with Great Expectations of this Cruize in particular. Why? I am pleased you asked!

My apologies, I misheard you. I thought when we heard the Three-Cheers from the Sailors in the Rigging of the Royal George it was the Signal to weigh Anchor. Evidently, I was mistaken. It being dinner time, I suggest we return to our Inn, where all the Comforts missing in our present Situation will no doubt be available to us for as long as required and perhaps some News as well.

§

You are restored by your nap, I trust? I see you have your Cloak with you—a wise Precaution against the Elements at Spithead, and a Shame you did have it with you this morning. However, you have no further need of it today. When you retired to your room after Dinner, I resolved to remain in the Public Rooms of The George, thinking that I should thereby come to some understanding as to the Reason for the Fleet’s delay. After all, there is no place better than a Public House when it comes to News and Gossip. And also Victuals—you must be in want of a Refreshment! Once we have arranged your light Repast, allow me to address your evidently unbridled Curiosity as to why the Channel Fleet has not left Portsmouth.

The News, my Guest, is this: The Seamen of the Fleet are refusing to go to Sea! I have ascertained that there have been extended Rumblings of Discontent for some time. Rumour has it that Anonymous Letters were sent to Officers of the Fleet in regard to the hardships of the common Sailors working His Majesty’s Ships. Another, necessarily Anonymous, Source revealed to me that, more recently, a Petition signed by a considerable number of Seamen was submitted to Admiral Bridport and the Port Admiral, Sir Alan Gardner, without any Result.

Moreover, I have learned that Admiral Bridport did give the Signal to leave for St. Helen’s, but he was defied. [12] I must admit I felt vindicated! I feared that your unpleasant Wait at the Spithead was due to a Blunder on my part. How could I possibly have anticipated a Mutiny?

You will no doubt be interested to hear how Bridport responded to the Insurrection of his Fleet. It was “With a steady and undaunted Mind” that his Lordship informed the Seamen that “he should enforce obedience to his Orders at the risk of his Life”. He also intimated that their Claims, “if respectfully and legally urged, should be submitted to the Admiralty Board, whose Decision, he was convinced, would be governed by the strictest Equity”. Naturally, his Lordship “conducted himself upon the Occasion in a Manner that must ever reflect the highest Honour upon his Character.”[13] Look, here is your Snack. Bon appétit!

As to the Reason for the Mutiny, it is my understanding that Royal George and the other 15 Ships of the Reserve Squadron anchored off the Spithead have seen no Action at Sea these past months. The Seamen have thus had ample time to stew on their low Wages and Disaffection with ship-board Conditions: including the Quality and Quantity of their Food; Treatment of the Sick and Injured; the Cruelty and Incompetence of some of the Officers; denial of Shore-Leave after returning from Sea; &c. &c. That said, my Source at The Ipswich Journal tells me the Officers and men are presently “on the best terms”.[14]

This Mutiny is a highly-organised Affair. I have it on good authority that its Delegates will submit a well-written Petition on Board H.M.S. Queen Charlotte, by the Delegates of the Fleet, next Tuesday, the 18th inst. In due course, you will be able to read a full Transcription of the Petition in Mr. W. J. Neale’s book on the Mutiny at the Spithead.[15] I predict the Petition will be accepted and Indemnity from Prosecution secured. Whether Bridport deserved to be commended for his Fairness or for his Prevarication, I cannot say.

As for the Implications of this momentous Event for your Ancestor, the Pay-Rise the Mutineers secure will see his Wage increase by £4 making a total of £47 per annum.[16] However, as a Midshipmen and now as Masters’-Mate, Mr. Greensword has already enjoyed some of the Privileges of Rank, including Shore Leave, for he found the time to marry.

The fact that H.M.S. Royal George has remained so much in Port this year can only have been a Blessing for our Newlyweds. A Dockland-Commission is much coveted by those desirous of spending time with their family. Of course, such Men have likely moved through the Ranks and enjoy an Officer’s pay. Young Mr. Greensword, R.N., on the other hand, is in need of Patronage, Promotion and Prizes!

In this regard, his present Ship simply will not do! In the coming months, H.M.S. Royal George will continue to wait to be despatched wherever Naval Intelligence sends her, which does not appear to be far afield. Meanwhile, Bridport’s Dispatches to the Admiralty Office, published in the London Gazette, consist mostly of Introductions to Letters he receives from Captains engaged in Action further abroad than the Channel, reducing the Flagship of the Channel Fleet to a glorified Packet! Does 70-year-old Admiral Bridport rest on well-earned Laurels or has he lost his Nerve? Whatever the case may be, he does little to advance Mr. Edward Greensword’s Career.

Fortunately, our young Masters’-Mate seems to have a Patron after all. He is Captain Wm. Essington, under whose command Edward Greensword sailed on the Sceptre and Moselle. On the 4th of June, 1797, Essington takes charge of the 74-gun H.M.S. Triumph, a Sail of the North Sea Fleet, which is under the Command of Admiral Adam Duncan. On the 14th of July 1797, Mr. Greensword is sent to the Triumph, remaining with this Ship until May 1798. It is not too long before he sees major Action off the coast of Northern Holland.

[1] Mr. Charles G. Harper, The Portsmouth Road and its Tributaries: To-day and in Days of Old, Illustrated by the Author, and from Old-time Prints and Pictures, London, Chapman & Hall Ltd. 1895, p. 30.

[2] The Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce, and Manufacture: Comprehending Lists of the Inhabitants of London, Westminster, and Borough of Southwark; and All the Cities, Towns, and Principal Villages, in England and Wales; with the Mails, and Other Coaches, Stage-waggons, Hoys, Packets, and Trading Vessels. To which is Added, a Genuine Account of the Drawbacks and Duties Chargeable at the Custom-house on All Goods and Merchandize, Imported, Exported, Or Carried Coastwise, with a Particular of the Public Offices of Every Denomination; His Majesty’s Court, and Ministers of State; the Peers of the Realm, and Parliament of Great Britain; the Court of Lord Mayor, Sheriffs, Aldermen, Common-council, and Livery, of London; Together with an Historical Detail of the Antiquities, Curiosities, Trade, Polity, and Manufactures, of Each City, Town, and Village. The Whole Comprising a Most Interesting and Instructive History of Great Britain, London, printed for the Patentees, and sold by Mr. C. Stalker, Bookseller, Stationer’s Court, Ludgate-street, and Messrs. Brideoake and Fell, Agents, MDCCXC [1790], p. 586.

[3] Mr. Charles G. Harper, The Portsmouth Road and its Tributaries: To-day and in Days of Old, Illustrated by the Author, and from Old-time Prints and Pictures, London, Chapman & Hall Ltd. 1895, p. 73.

[4] Mr. Daniel Paterson, A New and Accurate Description of all the Direct and Principal Cross Roads in Great Britain and Wales, &c., &c., eleventh edition, London, Printed for T.N. Longman, Pater-Noster-Row, 1796.

[5] Mr. William Connor Sydney, “Roads and Travelling”, England and the English in the Eighteenth Century, Chapters in the Social History of the Times, second edition, volume II, Edinburgh, Mr. John Grant, no. 31, George IV, p. 9.

[6] “Home News, Portsmouth”, The Hampshire Chronicle, Issue 1236, Saturday, 8th of April 1797, p. 4.

[7] Spithead is described as the “sea-road between the Isle of Wight and the Continent of Hampshire, and which, from Cowes to St. Helen’s, is nearly 20 miles in length, and in some places, three miles broad”, “Portsmouth Harbour” Mr. Mottley, The History of Portsmouth, Containing Its Origin, Progressive Improvements and Present State of Its Public Buildings … with an Account of the Towns of Portsea, Gosport … and the Isle of Wight: to which is Added an Appendix Containing the Names of All the Officers in the Naval, Military, Civil and Commercial Establishments, with a Commercial Directory to the Coaches, Waggons and Vessels that are employed in Portsmouth, Portsea, and Gosport, Portsmouth, printed for Mr. J. C. Mottley, Grand Parade, 1801, p. 50

[8] Mr. William James, The Naval History of Great Britain, from the Declaration of War by France in February 1793, to the Accession of George IV in January 1820; A New Edition with Considerable Additions and Improvements, including Diagrams of all the principal Actions, in Six Volumes, Volume 1. London, printed for Messrs. Harding, Lepard, & Co., Pall-Mall East, 1826, pp. 535‑536.

[9] Mr. Basil Luddock, The Blackwall Frigates, Messrs. James Brown & Son, Glasgow, 1922, p. 40.

[10] Seamen would have shared a pool of one quarter of the Prize Money, but they being the most numerous on a single Ship, let alone 5, it was no doubt a paltry Sum the Sailors received, good for little more than a rousing night at the Tavern. Reader, this might explain the loose Behaviour I observed when I went down for a Night-Cap last night.

[11] Reader, I have had little time to devote to the Work of discovering the Existence of a familial Connexion between Elizabeth Charrier, formerly Hopkins, and the new Mrs. Greensword.

[12] Another of my naval Consultants, Mr. Stuart Waters, from the Kent History Forum, has since told me the Three Cheers we heard “was the signal for the Mutiny to begin and as one, the men of every ship in the Channel Fleet refused to weigh anchor as ordered.” Reader, you may read more about the Mutiny in Mr. Waters’ entry on H.M.S. Queen Charlotte, which is the sister-ship to H.M.S. Royal George by consulting the good Folk at the Kent History Forum.

[13] Reader, I generally do not report either my own or my Client’s speech in inverted commas. In recounting my Narrative at breakfast that morning in Portsmouth in the Present work, I have eschewed my Recollection of the Facts I gleaned from the various Seamen I encountered the previous evening in The George. Instead, I draw on a contemporaneous Written Record. I have no doubt it was for the sake of Truth & Accuracy that I kept my copy of The Ipswich Journal, dated Saturday 22nd of April 1797, Issue no. 3360!

[14] The Ipswich Journal, Saturday 22nd of April 1797, no. 3360.

[15] Mr. William Johnson Neale, History of the Mutiny at Spithead and the Nore: With an Enquiry Into Its Origin and Treatment; and Suggestions for the Prevention of Future Discontent in the Royal Navy, London, Printed for Thomas Tegg, no. 73, Cheapside, 1842, pp. 28–29.

[16] Mr. Evan Wilson, A Social History of British Naval Officers, 1775–1815, Boydell and Brewer, Boydell Press, 2017, p. 142.