At Sea • 17th of October, 1820, a Tuesday

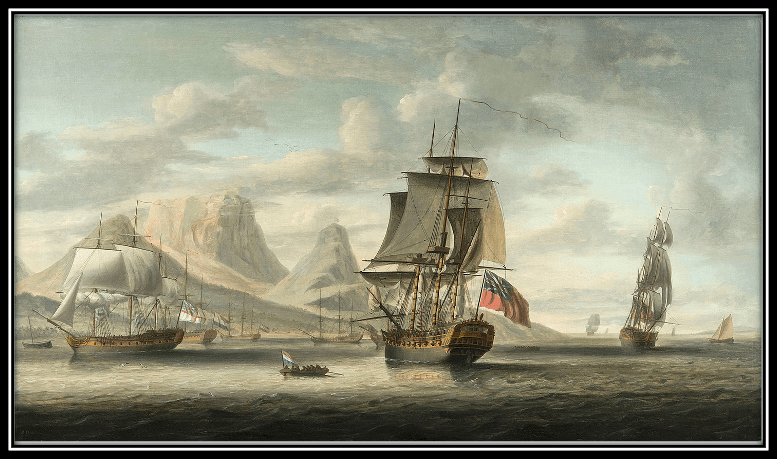

Reader, we left Table Bay 3-days ago, this harbour so-named for the mountain that overlooks Cape-Town. We were there for 15-days, having been towed into port early on the morning of the 28th of September.

The Tourist and I were not the only passengers looking forward to trying our shore-legs, but there had been an outbreak of the Measles on-board, and even though there had been no new cases for 3-weeks, the Captain was obliged to hoist the Quarantine-Flag. All aboard were forbidden to leave the Skelton.

According to ship-board rumour, later verified by Capt. Dixon, “the disease began in the family of Mr. Headlam, and had been communicated to that family by travelling in the same coach from London, with a child that had just recovered”.[1] The source of the disease seemed to come as no surprise to my Client, who was not as much put out by the epidemic—which afflicted 36 children and 5 adults—as I would have thought, having apparently survived the Measles as a child. I nevertheless deduced a modicum of Gratitude that I had not purchased our passages in Steerage.

What did exercise my Client was that, being prohibited from disembarking in Cape Town, it was not possible to procure particular Victuals or to wash our linens or, indeed, ourselves.

The Skelton’s supply of water did not extend to regular laundering, and the Cape Town Health Officer and the Colonial Secretary categorically forbade washing ashore for fear of contamination from the soiled linens belonging to the victims of the Measles. As to fresh Victuals, we discovered that those familiar to the Tourist were expensive, and of oranges and lemons, of which that individual was most desirous, there were practically none.

You see, my Companion seems to have developed a debilitating fear of the Scurvy. Such a fear, I agree, is not unfounded, but the Captain makes Brewer’s Malt, Sour-Crout, Vinegar, Mustard and Portable Soup freely available to all passengers and crew. These measures, however, do not satisfy one person among them.

Figure 2: Southampton anchored off Cape Town with Table Mountain in the Distance, Mr. Robert Dodd, oil on canvas, 32 and 7/8 in. x 56 5/8 in., 1786. Needless to say, the ships at anchor in 1820 do not look quite the same as those in this picture, but Table Mountain does.

For my own part, I am simply grateful that our ship took on a generous supply of fresh mutton. I am heartily sick of salted meat and glad even of a temporary respite. The Captain also bartered some hops for Holland Gin, which was much enjoyed by all who attended the dance on the eve before our departure, including my humble self.[2]

I regret to report that no sooner had we rounded the Cape Point than we found ourselves in rough seas. Captain Dixon predicts more to come. My Companion has been confined to cabin ever since. Perhaps this is for the best, for this person has become increasingly irritable as our voyage progresses.

In one overheated conversation, the Tourist even claimed that my Presumption in booking Passages without consultation went beyond the pale, since “everyone” knows the high seas are dangerous.

But, as I pointed out, had we remained in Portsmouth, we would learn nothing about Mr. Wordley’s immediate future for quite some time. Besides, to the best of my knowledge, none of my Client’s other Relatives will be doing anything of slightest historical interest for the duration of our absence.

Port Jackson • January 18th, 1821, a Thursday

We have finally arrived at our destination! To be frank, Reader, I had no idea the journey would take so very long. We left Portsmouth 3-weeks to the day before Mr. Wordley and have arrived 4-weeks after he! Admittedly, our Itinerary took us by way of Van Diemen’s land.

We landed in Hobart-Town late afternoon on the 26th of November. Many of our fellow passengers left the Skelton here, including the late Mr. Road-Knight, an elderly man, who died on the night of the 25th, leaving his two sons, a daughter-in-law, and five grandchildren in a state of great distress. He had been poorly for much of the trip and I had not seen him since the Cape.

We bade fond farewells to our shipboard Friends, little realising that we would find ourselves bumping into them time and time again on the streets of Hobart-Town. I admit to suffering severe embarrassment, and before the week was out, I was hard-pressed to justify the extended lay-over to my Client, since I had not revealed the fact that I had been unaware of its duration when I booked our passage.

It did not help matters that the price of Lodgings is inflated in Hobart-Town. We remained until the 5th of January, seeing such sights as were recommended to us and passing a very quiet and rather queer Christmas.

Figure 3: “This SOUTH WEST VIEW OF HOBART TOWN VAN DIEMANS [sic] LAND is respectfully dedicated to the RIGHT HONORABLE [sic] EARL BATHURST/His Majesty’s Principal Secretary of the State for the Colonial Department, by the Publisher/London, Published March 1st 1820”, Mr. G.W. Evans, engraver. Engraving and aquatint, printed in black ink, from one plate; hand-coloured, 14 in. x 21.5 in. Centre for Australian Art NGA.

The next leg of our journey brought an unwelcome resumption of heavy seas driven by a strong gale. My Companion retired to below decks once more. We arrived at Jervois Bay on the 10th, and Captain Dixon told those of us at dinner that night that we would be in Sydney the next day.

This was not to be. There were yet more gales, and the winds being against us, the Skelton did not get off the Heads for another week, finally entering Sydney Cove on the 17th of January 1821.

Figure 4. View of the Heads at the Entrance to Port Jackson New South Wales, Mr. Joseph Lycett. Aquatint, hand coloured, plate mark 9in. x 13in. London, no. 73, St. Paul’s Church Yard, published by Mr. J. Souter, 1st of October, 1824.

We disembarked this morning and found good Lodgings. We sent our clothes out for laundering and each took a bath. At dinner, my Client’s request for a Salat of raw vegetables followed by miscellaneous fresh fruits was accommodated, mercifully without raised eyebrows. I was surprised no request was made for oranges and lemons.

Now that this person has gone to bed, I shall deliver my account of the Hebe’s arrival at Port Jackson.

Reader, you may be surprised to know I was able to ascertain this information while we languished at the Port Jackson Heads—thanks to my Informant, who sent word by one of the small craft that periodically waited on the Skelton. The letters were a great tonic against boredom!

According to my contact in the settlement, the Hebe arrived in Port Jackson on Sunday the 31st of December 1820:

At 1. P.M. the same day anchored in the Harbour the Ship Hebe Commanded by Capt. R. Wetherall, with 158 Male Convicts on board from England, whence She Sailed on the 10th. of August last; Dr. Carter R.N. being the Surgeon Supdt.—and the Guard, consisting of 1 Serjt. & 30 Men of the 48th. Regt., being Commanded by Lieut. Campbell of the 59th. Regt. The Hebe on her Passage hither touched at Rio, and remained there for Ten Days.—[3]

The Convicts did not disembark until Thursday, 11th of January 1821. What delayed their disembarkation, you ask?

There were already convict ships in Sydney Cove when the Hebe arrived, and the prisoners aboard the Almorah and the Asia had to be disembarked before those on the latest arrival. Moreover, a Muster had to be conducted. This generally takes place on the Quarterdeck and is conducted by the Governor’s Secretary, Mr. John Campbell, and the Superintendent of Convicts, Mr. Wm. Hutchinson, in the presence of the ship’s Captain and the Surgeon Superintendent.

Mr. Bigge has kindly supplied me with a sneak peak of the description of this procedure in the manuscript of the Report on the State the Colony, which he will table 2-years’ hence to the House of Commons:

Each convict is asked his name, the time and place of his trial, his sentence, native place, age, trade and occupation; and the answers are compared (and corrected if necessary) by the description in the indents and in the lists transmitted from the hulks. After ascertaining the height of each convict by actual admeasurement, and registering it in several columns, as well as the colour of the hair, eyes, the complexion or any particular mark that may tend to establish the identity of each convict, an inquiry is made respecting the treatment that each has received during the passage, whether he has received his full ration of provisions; whether he has any complaint to make against the captain, his officers and crew; and lastly, whether he any bodily ailment or infirmity. A further inquiry is made of the surgeon, respecting the conduct of each convict during the passage, and whether he has any bodily infirmity that may prevent him from being actively employed.[4]

Because Mr. Isaac Wordley goes through the correct procedures, I can tell you that he is a man of good height, being 5-foot, 10-inches tall, with a fair to ruddy complexion, brown hair and hazel eyes.[5]

It is only once the Muster has been completed that the day of disembarkation can be appointed, and since it is at the Governor’s pleasure, it is no doubt scheduled so as not to interfere with other gubernatorial duties including attendance at luncheons, Church services, &c. &c.

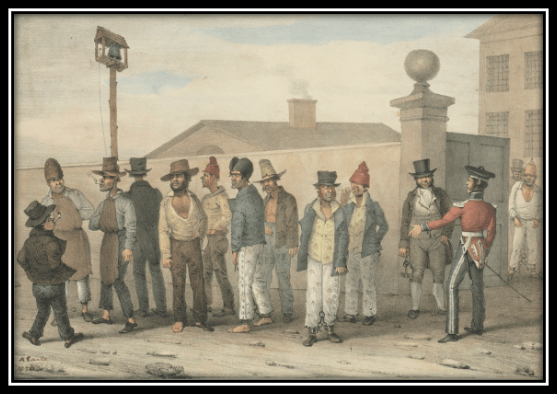

On Thursday, the 11th of January 1821, the prisoners on the Hebe put on their new clothes, which consist of a “cotton shirt, white ‘duck’ trousers, a blue coarse woollen jacket, a yellow and grey waistcoat, stockings and shoes, a neckerchief, and a woollen or leather cap, all clearly marked with the government ‘broad arrow’ and the letters ‘P.B.’ (Prisoners’ Barracks)”.[6]

Figure 5: “A Government Gaol Gang, Sydney, N. S. Wales”, Mr. A Earle, in Views in New South Wales and Van Diemens [sic] Land, Australian Scrap Book, 1830, published by Mr. J. Cross, London, 1830.

After they were disembarked, the convicts marched to the yard of the gaol in Sydney, where they were inspected by Governor Lachlan Macquarie. They were then assigned duties: some, known as the “Government Men”, typically tradesmen, will contribute to the building of Sydney-Town. They will sleep on flax hammocks in the great whitewashed dormitories in the Hyde Park Barracks and be given a ration of 7lbs. of meat and the same of quantity of flour per week.

Clerks, Shoemakers, Tailors, and other such tradesmen not required for Government works are assigned to Overseers. Some such convicts with some money of their own may be able to secure a Ticket-of-Leave to conduct a business of their own. Others again are allocated to Free Settlers that have lodged an Application for Government Servants.

In the present instance, Mr. Wordley and 5-other men have been assigned to the Magistrate responsible for the distribution of Convicts in Parramatta, Mr. H. H. MacArthur. The Tourist and I will relax in Sydney-Town for a spell before we follow them there.

[1] Captain James Dixon, Narrative of a Voyage to New South Wales, and Van Dieman’s [sic.] Land: In the Ship Skelton, During the Year 1820, With Observations on the State of these Colonies, and a Variety of Information, Calculated to be Useful to Emigrants, printed for Mr. John Anderson, Jun., no. 55, North Bridge-St., Edinburgh, and Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, London, 1822, p. 2.

[2] Captain James Dixon, Narrative of a Voyage to New South Wales, and Van Diemen’s Land, &c, &c., p.24.

[3] Mr. Charles Bateson & Library of Australia, The Convict Ships, 1787-1868, Sydney, Library of Australian History, 1983, pp. 344-345, 383.

[4] Mr. John Thomas Bigge, Report of the Commissioner of Inquiry into the State of the Colony of New South Wales, ordered by the House of Commons, to be printed 19th June 1822.

[5] Well, these are the clothes said to be worn by the convicts on the First and Second Fleets. New South Wales State Archives, Indents First Fleet, Second Fleet, and Ships, NRS12188, microfiche 645, State Records Authority of New South Wales, Kingswood, New South Wales.

[6] “A Day in the Life of a Convict, 1820”, Sydney Living Museum, https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/convict-sydney/1820-day-life-convict.